TMJ

Abbreviation for TemporoMandibular Joint (joint on either side of the head where the jaw bone meets the skull, situated just in front of the ear)

A quick way of referring to dysfunction in the Temporomandibular joint, which are sometimes abbreviated as TMJD or TMD

Temporomandibular joint and muscle disorders (TMJ disorders) are problems that affect the chewing muscles and joints that connect your lower jaw to your skull.

Temporomandibular dysfunction (TMJ) is a very common condition and can be oh so debilitating for those that suffer from it. I described my personal TMJ journey in another post, and I happily admit that for many years I didn’t really know that I suffered from TMJ and that anything could be done about it other than taking the combination of pills that worked for me. This post is looking in more depth about the joint and also the symptoms and possible causes of TMJ.

The TMJ is the joint between the jaw bone (mandible) and the temporal bones of the skull. This joint can be found just in front of the ear on each side. Don’t press too hard as it can be very, very tender.

The jaw bone is interesting in that it is the only bone in the body that we consciously move that crosses the midline of the body without forming the midline of the body (i.e. the bones of the spine). So in some schools the jaw can help to maintain tension elsewhere in our bodies, but I’ll come back to this later on in the post.

The jaw is quite a complex joint, as it behaves like a hinge joint for the first part of opening the mouth, but then slides to allow greater opening. It contains its own cartillagenous disk that helps to maintain space, which can cause problems if there are issues with how this moves. The jawbone also has limited side to side movement as well, which helps us to chew and grind our food.

Classically, there are said to be four muscles that directly work on the TMJ:

- Temporalis, which is the big fan like muscle that sits above the ears, and is often typically massaged when someone has a headache. This helps to close the mouth, bringing the teeth together.

- Masseter, which is the big muscle on each side, which is really quite powerful, that also helps to bring the teeth together.

- Medial Pterygoid, which is quite a small muscle that also helps to bring the teeth together. This is not any easy muscle to find, as it is on the inside of the jaw.

- Lateral Pterygoid, which is a two headed muscle that is also easiest to feel from inside the mouth, and is the only one of the four that moves the teeth apart.

We need the greatest power to close the jaw and chew on our food, which is why there are more muscles that close the jaw than open. This is also true in animals with the crocodile having a massively powerful bite but very weak mouth opening muscles (so their jaws can be held closed with very little effort, but I’m not going to try this one out myself.)

Running through this area is the trigeminal nerve, which is one of the cranial nerves. It passes very close to the TMJ itself and then separates into three main branches: one goes to above the eyes, the second runs under the cheek bone along the top teeth, and the third runs down onto the mandible and along the teeth. This is why the joint can cause a lot of feelings of pain in the face and the teeth, which is something I know all too well.

Like many parts of the body, the bones and muscles are really quite well organised when working well and they can cope with a lot. However, long term adaptations and disruptions can creep in and we end up with issues. These issues are a group of symptoms that are referred to as TMJ Dysfunction (TMJD) but mostly as just TMJ.

What are the symptoms of TMJ?

TMJ can have a very wide range of symptoms that are not just confined to the space in front of the ear, but extend into the face and neck. The following is a list of possible symptoms that have been attributed to TMJ:

- Head, jaw, and/or face pain.

- Headache.

- Popping, clicking or grinding in the joint.

- Deep jaw discomfort.

- Difficulty in opening, moving the jaw and closing the mouth. Including difficulty speaking.

- Trismus, or locking or limited opening of the jaw.

- Bruxism (grinding the teeth) or clenching the teeth.

- Tinnitus.

- Dizziness or vertigo

- Earache, without any infection

- “Glop in the throat” or a feeling that something is stuck in the throat.

- Sleep issues and disordered sleep.

- Photosensitivity (dislike of bright lights) and a sensitivity to certain loud sounds.

As you can see there are so many possible symptoms, and you don’t need to suffer from them all to be troubled by TMJ. This list comes from the TMJTherapy® website. I’m almost certain that I will find other issues that prove to be a symptom of TMJ, or TMJ issues are a contributing factor.

What causes TMJ?

Like the symptoms, the possible causes of TMJ are vast. But, again according to the TMJTherapy® website they may include:

- Poor bite alignment

- Poorly fitting dentures/crown/implants

- Occlusal imbalances (malocclusion)

- Displacement of TM discs the cartilaginous discs between the Temporal bone and the mandible.

- Extensive dental work including extractions where lots of pressure placed on the TM joints.

- Chronic clenching or grinding

- Chewing gum on a regular basis as we tend to chew on the same side.

- Accidents, especially one that had a whiplash like event.

- Extensive phone use, especially if you hold the phone between ear and shoulder.

- Intubation during surgery or induced comas. You have a breathing tube inserted when you are attached to a machine for surgery or induced comas (which is something very much on my mind during the Covid pandemic as so many people have ended up in ICU on respirators.)

- Malformations of the head, neck or facial bones.

- Chronic illness such as Chronic Fatigue Syndrome, Fibromyalgia, Lupus, Rheumatoid Arthritis or sleep disorders.

- Stress and its attendant postural changes, which is my trigger.

These possible causes are not exhaustive and many of us can experience many of them and not suffer any problems. That variability and the fact that each of us experiences the feeling of pain differently makes it hard to say that a person who has any dental surgery will suffer from TMJ. They may have many contributing factors that overlap each other and the dental work they have done just pushes them over the edge; or they have the dental surgery and the adaptations they adopt post surgery ultimately lead to an imbalance in the muscles that causes TMJ symptoms years later.

TMJ is a whole body issue

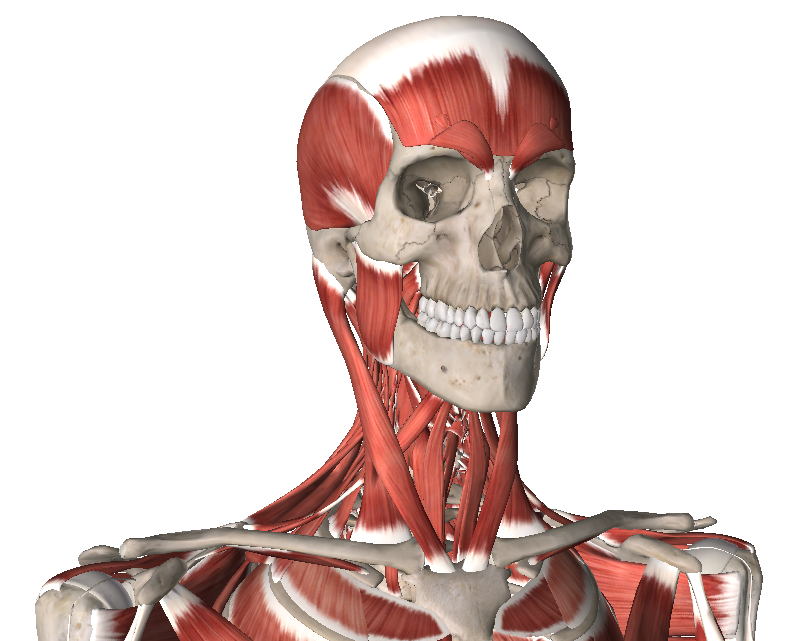

One other massive potential cause of TMJ problems is stress. This can affect not just our jaw but is a something that affects the whole body. You do also need to remember that muscles are typically shown in a similar way to the picture above as clean and seperate things, this is because they are easier to visualise, but in actuality they are surrounded by the fascia and connective tissue, which helps to contain them and also spread the forces between different areas and structures. This fascia can slowly adapt to changes in the tensions of the muscles and connective tissue so the muscle fibres don’t have to work as hard.

If you look at the image of the skeleton and muscles again you can see that there are many muscles that extend down from the jaw area to the top of the breast bone. There is a bone, called the hyoid bone, floating at the front of your throat just underneath the mandible. This bone floats in a network of 12 different muscles which form connections with the jaw, the skull, the tongue (which is just a large muscle), the breast bone, and even as far as the scapula (or shoulder blade).

You can also see there are muscles the connect just behind the ear down to the collarbone and the breastbone, the sternocleidomastid (abbreviated to SCM). In my experience the majority of people spend a lot of time with their head forward over their breast bone, basically in response to modern life of hunching over computers and phones (See this blog on how to set up your workstation to help minimise this). This head forward position seems to help the SCMs and the surrounding fascia become shorter and so less able to respond. The skull is also held forward of the gravity line that allows the vertebrae to support the structures of the skull and that means the muscles of the back of the neck and body have to work harder. The head forward position also means that the tensions through all of these muscles stop the jaw being held in a truly neutral position and could possibly have to over use muscles (particularly the temporalis bone) to keep our mouths closed.

Quick assessment:

- Either lie down, or sit with the back of your head resting lightly against the floor/wall.

- Without hurting yourself, open your mouth as wide as you comfortably can.

Do you have to tilt your head to fully open the mouth? Especially right towards the end. You might have heard your hair sliding against the surface behind you.

If you do have to move your head , the temporalis muscle is tighter than is helpful, and you have altered your movement to achieve the objective of opening your mouth.

A deeper connection from TMJ to Pelvis

So far, I’ve briefly mentioned the muscles and fascia that connect the jaw and skull to the rest of the body, but there is a deeper connection between the TMJ, the skull and the pelvis. This is the dural membrane and tube which surrounds and protects the central nervous system of the brain and spinal cord. The dural membrane is firmly attached to the interior of the cranial bones (which surround the brain) that include the temoporal bones, and the sphenoid bone. Remember that the temporal bone is the T of TMJ, so directly linking the jaw joint to the brain casing. The pterygoid muscles are attached between the sphenoid bone and the mandible, so a soft tissue connection to the jaw.

The dural tube then extends down into the spine to surround the spinal cord, and the dural tube is mostly freely moving within the spinal canal all the way down until the sacrum, which is the back of the pelvis, where it is firmly attached to the bone. The dural tube can then be considered to potentially act as a pulley system between the cranium and the sacrum. It is referred to as the Cranio-Sacral theory.

There is the concept of Cranio-Sacral theory, in that what happens in the head happens in the pelvis and vice versa. So if someone always crosses their legs in one direction this might put a twist or torsion into the pelvis, which means that the dural tube is tugged on one side of the sacrum. This tug on the dural tube is said to then tug on the occiput bone at the base of the skull, which is the next place that the dural tube is firmly attached, and then the bones of the cranium. The temoporal bones and the sphenoid bone of the cranium can then be gently tugged and the muscles that connect these to the jaw can cause the jaw to move in a less than optimal way.

This is why I consider the pelvis when working with people with TMJ, and also consider the jaw when working with people with persistant back pain.

TMJ is a huge subject and can touch on so many areas of our lives. I feel like I could have written a lot more and that I’ve glossed over some incredibly important things. However this is a blog post and not a book so I’ve tried to keep it brief.

Thanks for reading this, my lovely Interonauts.

Tim

Bibliography

These books and articles have significantly influenced my view on the Myofascial Network. I am also doing my best to stay on top of current research and so my opinions will change as new information comes to light.

- Barnes, John F. (1990) Myofascial Release: the search for excellence, Rehabilitation Services Inc

- Barnes, John F. (2016) Myofasial Release: Healing Ancient Wounds, the Renegade’s Wisdom, (2nd Edition) Rehabilitation Services Inc

- Barnes, Mark (1997) The Basic Science of Myofascial Release: morphologic change in connective Tissue, The Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies.

- Chaitow, Leon (ed) et al. (2014) Fascial Dysfunction. Manual Therapy Approaches, Handspring Publishing

- Covell, Cathy (unknown publication date) A Therapist’s Guide to Understanding John F Barnes Myofascial Release: Simple Answers to Frequently Asked Questions

- Duncan, Ruth (2014) Myofascial Release – A step-by-step guide to more than 60 techniques. Human Kinetics

- Earls, James & Myers, Thomas (2010) Fascial Release for Structural Balance. Lotus Publishing

- Guimberteau, Jean-Claude & Armstrong, Colin (2015) Architecture of Human Living Fascia: The extracellular matrix and cells revealed through endoscopy, Handspring Publishing Ltd.

- Juhan, Deanne (2003) Job’s Body: A handbook for bodywork, Barry Town/Station Hill

- Myers, Thomas (2009) Anatomy Trains: Myofascial Meridians for Manual and Movement Therapists. 2nd Edition. Churchill Livingstone.

- Pollack, Gerald (2001) Cells, Gels and the Engines of Life, Ebner and Sons Publishers

- Scarr, Graham (2014) Biotensegrity. The Structural Basis of Life, Handspring Publishing

- Schleip, Robert (2003a) Fascial plasticity – a new neurobiological explanation: Part 1, Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies, Elsevier Science Ltd

- Schleip, Robert (2003b) Fascial plasticity – a new neurobiological explanation: Part 2, Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies, Elsevier Science Ltd

- Schleip, Robert et al. (2012) Fascia: The Tensional Network of the Human Body. Churchill Livingstone

- Schleip, Robert et al (2014) Fascia in Sport and Movement, Handspring Publishing

- Schleip, Robert & Bayer, Johanna (2017) Fascial Fitness: How to be Resilient, Elegant and Dynamic in Everyday Life and Sport, Lotus Publishing

- Schultz, R. Louis and Feitis, Rosemary (1996) The Endless Web: Fascial Anatomy and Physical Reality, North Atlantic Books

- Tavolacci, Phil (2013) What’s in your web: Stories of Fascial Freedom, Balboa Press