Everybody hurts…

…but may not feel it in the same way.

In May 2019, I spent one of my weekends sitting in a room with 250 other health professionals (including surgeons, physiotherapists, doctors, psychologists, and massage therapists) listening to Professor Lorimer Moseley giving his “Explain pain” talk. I have since followed this up with the book he wrote with David Butler also called Explain Pain, which is why this post has taken a while to appear.

It was a fascinating weekend and Lorimer Moseley is an excellent speaker, keeping a disparate group of people with varying levels of knowledge and understanding focussed and understanding an incredibly complex subject. The weekend was aimed at sharing some of the most recent pain science and to get thinking about what pain is and how to alter our relationship with it. There are a couple of videos of him talking and they are well worth looking at: Why things hurt, and Body in Mind: the role of the brain in chronic pain. If you are in the health industry and get the change to see him speak I would strongly urge you to go.

The whole subject of pain is a huge one, and I’m sure that it will be something that I will be circling back to again and again, as resolving/releasing/getting rid of pain is why most people come to see me about. I will try to share what I have learnt from the talk and also the book, and any errors that creep in are down to me.

So first, have a think about how you would define what pain is.

It’s a tricky question and one that we were posed fairly early on in the weekend. Lorimer Moseley put forward the following definition:

Pain

An unpleasant feeling somewhere in the body that urges us to protect our selves.

It’s a fascinating definition and I will try to unpick it, at least a bit. I will probably have many more posts around the subject.

Pain is an output from the brain

Our bodies are covered by many, many, many, many nerve endings that pick up different conditions in our body: heat, cold, chemical damage, pressure, stretch, and many more. Things like chemical damage, puncture to the skin are picked up by sensors that respond to threats to the body, these are called nociceptors. All of these sensors only detect one condition, so a nerve ending that detects heat does not detect pressure. The sensor will only send a message upwards to the brain when a particular temperature threshold/event happens, e.g. touching a hot kettle. If only one sensor is triggered, we are unlikely to feel pain, whereas when many sensors send a message we will respond.

Many of these sensors are constantly send messages towards the central nervous system (spine and brain), but their message is ignored as it not considered a threat. For example, if you are sitting on a chair the weight of your body is squashing the soft tissue of your gluteal area: in the short term this is unlikely to cause injury so it is ignored and we don’t actually notice the amount of pressure on our buttocks unless we’ve been there for such a long time that other sensors are triggered.

The triggering of multiple sensors will send a warning message upwards to the brain for interpretation. So for the example of touching a kettle, the area being affected by the heat will cover more than one heat sensitive nerve cell, and there may be cellular damage which releases chemicals that should remain in the cell and these irritate the nerves that detect chemical threats. This combination of messages will not be normal for the system and so a message is sent to the brain for interpretation, the brain reacts and we feel pain. In this example, there can be a reflexive movement away from danger, which is a protective motion triggered at the spinal cord, with a message being sent upwards to the brain. This is the cause of the delay in feeling and reacting to a reflexive action.

However, the nociceptors (threat detectors) in the body are not sensing pain, they’re detecting a specific threat to the system. The feeling of pain is actually our brain interpretting the signals and responding to protect the body from harm often with a movement away from further injury. So, in short all pain is in your head. I have always disliked it when people say that someone’s pain is “psychosomatic”: it all is, just some are more sensitive to it than others.

Pain is actually our body protecting itself, and should be celebrated. Even though pain is really annoying, it is actually a good thing: it could be worse if you didn’t feel anything. It is possibly to badly burn yourself leaning against a warm radiator, the temperature isn’t too threatening, but if the body can’t cool itself there might be damage to the cells with the constant above blood temperature of the radiator. It would take some time, but if the body keeps ignoring it then it can really hurt you.

Pain is protective

As I said above, the feeling of pain is a protective response to information that says we are heading towards danger. Pain is the early warning klaxon ringing in our brains to say that if we keep doing that we could potentially harm ourselves. There is a threshold to which our damage sensors react to with the understanding that we will move away from the source of the feeling of pain. Again, the fact that we feel pain is theoretically a good thing, although I know that may be of limited comfort to people suffering from chronic pain.

There are times when we don’t feel pain but we are injuring yourself: sunbathing is the one that comes to mind. For many people we enjoy the warmth of the sun on our skin, and we don’t actually feel the damage the UV rays are inflicting on our skin until we’ve had more than we should (if then). Unless you’ve been burnt really badly and then you might start to feel uncomfortable sooner than someone who’s skin seems to not react. Being a red head I’m more careful than others as I’ve been burnt too many times, but I do still get it wrong.

If we keep hurting ourselves, the body can adapt so that it starts to sound the warning klaxon far sooner than the original safe threshold. It starts to anticipate pain because certain signals are being recieved and we are in a particular environment. I have come across this with people who have had a traumatic injury (often many years prior to seeing me) or who have had very vigorous treatments that triggered flare ups or just re-inforced a feeling of pain in an area. As I’ve worked closer to the area of pain or injury they start to mention pain or tense up as they are expecting it to hurt. This is part of the reason I work more softly and encourage people to tell me if it feels too much. I will probably go further into this in a different post, soon.

Sometimes the protective system becomes too sensitive and we respond to things that aren’t even threatening to us as if they are a threat. This can be because we have started to anticipate the potential pain; or the situation we find ourselves in is making our systems go onto high alert. The brain can even feel pain in a part of the body that is no longer there: this is the phantom limb pain that amputees can suffer from. There are so many potential influences on the way our brains perceive pain that I will have a look the model that Lorimer Moseley uses to explain this in a different post.

However I will share a quote from Lorimer Moseley that I think sums us up as humans:

“We are fearfully, wonderfully complex“

Lorimer Moseley

Pain is a massive topic, and I feel like I’ve barely scratched the surface. It is probably a subject to which there are thousands of books, and research articles (and many journals) devoted to, so I don’t feel like I’m doing too badly.

One thing that I do encourage my clients to do whilst I’m working with them is to actually thank their bodies for letting them know about a potential threat; to acknowledge that the part of the body that is in pain is doing it’s job. And maybe that area can try to turn down the response (especially true of tight muscles) to a more appropriate level to see if the threat is still present. It seems to help some people.

This is a massive subject and I know I will be returning to it in the future. There are so many ways of describing pain, and also how we can experience pain in different circumstances and situations to different levels.

Thanks for reading this, my lovely Interonauts.

Tim

Books, websites and other resources

Moseley, Lorimer & Butler, David (2013) Explain Pain (2nd Edition), NOI Group Publications

Moseley, Lorimer & Butler, David (2017) Explain Pain Supercharged, NOI Group Publications

Moseley, Lorimer & Butler, David (2015) The Explain Pain Handbook Protectometer, NOI Group Publications

On a lighter note:

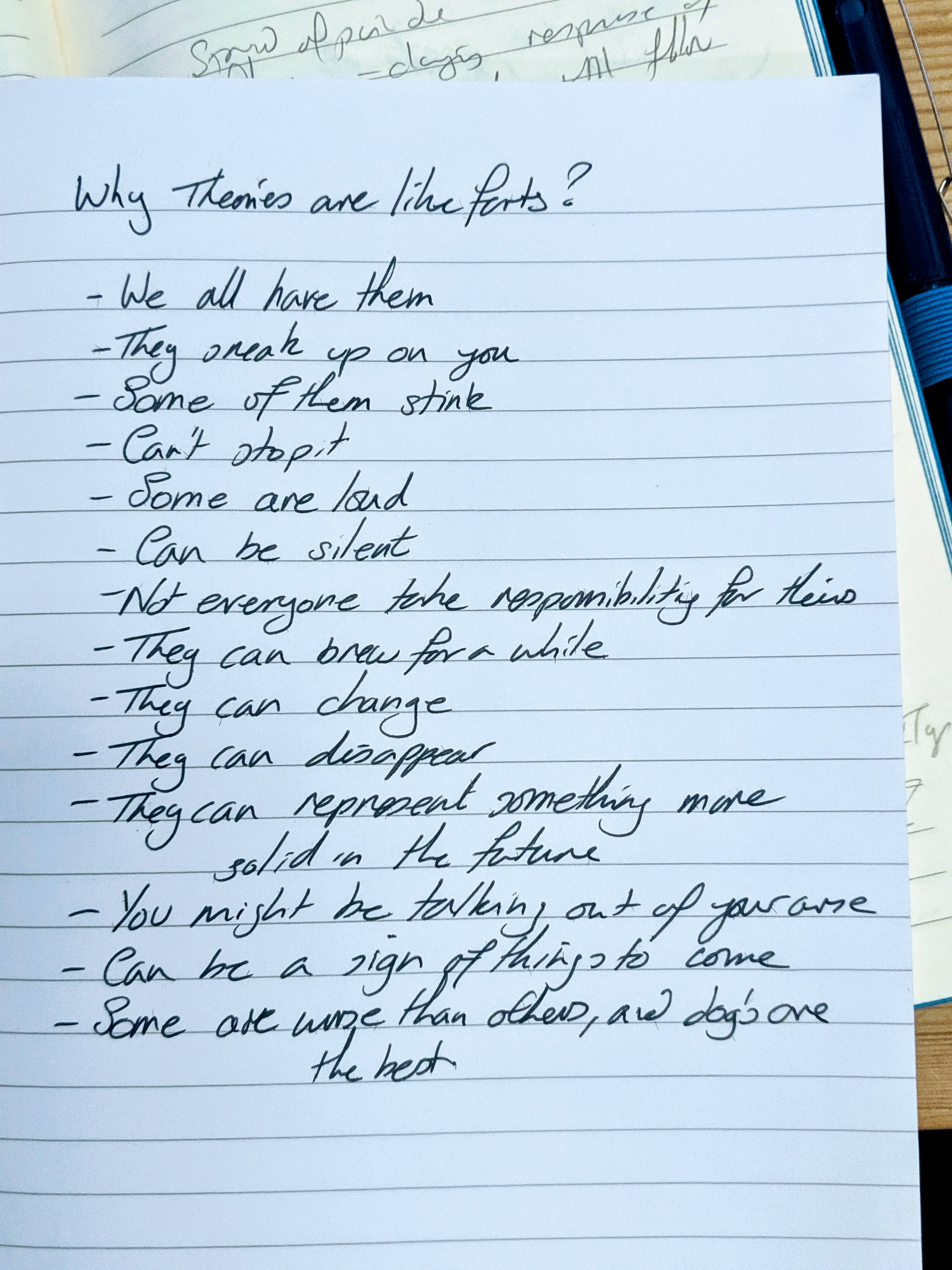

As part of the course we worked in groups to answer the question “Why Theories are like farts…”, the group I was in came up with the most, so I had to stand up and read this list out.

UPCOMING IN 2020

Reiki Courses: I’m running a Reiki Level 1 course running in March 2020. More information (External website)

British Fascia Symposium: Bi-annual conference sharing information about the Fascia and it’s applications in clinics. More Information (External website)